THE SORROWLESS FLOWERS

Thiện Phúc

VOLUME II

291. Bồ Tát là Ai?—Who is a Bodhisattva?

292. Tứ Thánh—Four Saints

293. A La Hán—Arhats

294. Ngũ Tịnh Cư Thiên—Five Pure-Dwelling Heavens

295. Lục Dục Thiên—Six Desire Heavens

296. Thập Nhị Dược Xoa Đại Tướng—Twelve Yaksha Generals

297. Thiên Long Bát Bộ—Eight Classes of Divinities

298. Tứ Thiền Thiên—Four Dhyana Heavens

299. Tứ Thiền Vô Sắc—Four Formless Jhanas

300. Tứ Thiên Vương—Four Heavenly Kings

301. Thập Thiện Nghiệp và Thiên Đạo—Ten Good Actions and Deva-Gati

302. Đạo—The Way

303. Tam Đạo—Three Paths

304. Đạt Đạo—Attainment of the Way

305. Thông Đạt Phật Đạo—Actualization of the Buddha’s Path

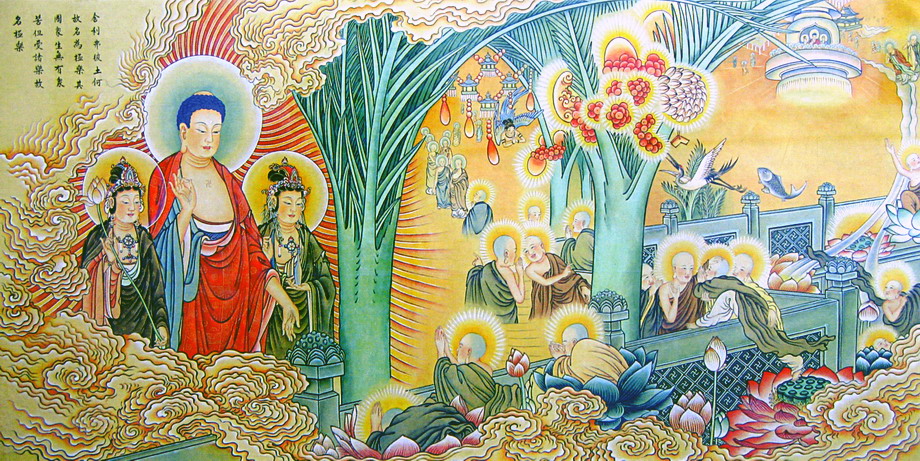

291. Who is a Bodhisattva?

“Enlightened Being” (Bodhisattva) is a Chinese Buddhist term that means an enlightened being (bodhi-being), or a Buddha-to-be, or a being who desires to attain enlightenment, or a being who seeks enlightenment, including Buddhas, Pratyeka-buddhas, or any disciples of the Buddhas. An enlightened being who does not enter Nirvana but chosen to remain in the world to save other sentient beings. Any person who is seeking Buddhahood, or a saint who stands right on the edge of nirvana, but remains in this world to help others achieve enlightenment. One who vows to live his or her life for the benefit of all sentient beings, vowing to save all sentient beings from affliction and aspiring to attainment of Buddhahood. One whose beings or essence is bodhi whose wisdom is resulting from direct perception of Truth with the compassion awakened thereby. Enlightened being who is on the path to awakening, who vows to forego complete enlightenment until he or she helps other beings attain enlightenment. A Bodhisattva is one who adheres to or bent on the ideal of enlightenment, or knowledge of the Four Noble Truths (Bodhi), especially one who is aspirant for full enlightenment (samma sambodhi). A Bodhisattva fully cultivates ten perfections (thập thiện—Parami) which are essential qualities of extremely high standard initiated by compassion, understanding and free from craving, pride and false views. There are five Bodhisattvas who have cultivated over countless lifetimes and expand in his life for the benefit of others. Therefore, a Bodhisattva is one who is enlightened, literally he is an Enlightenment-being, a Buddha-to-be, or one who wishes to become a Buddha. It would be a mistake to assume that the conception of a Bodhisattva was a creation of the Mahayana. For all Buddhists each Buddha had been, for a long period before his enlightenment, a Bodhisattva. But why does a Bodhisattva have such a vow? Why does he want to undertake such infinite labor? For the good of others, because they want to become capable of pulling others out of this great flood of sufferings and afflictions. But what personal benefit does he find in the benefit of others? To a Bodhisattva, the benefit of others is his own benefit, because he desires it that way. Who could believe that? It is true that people devoid of pity and who think only of themselves, find it hard to believe in the altruism of the Bodhisattva. But compassionate people do so easily.

According to the Mahaprajnaparamita sastra, Bodhi means the way of all the Buddhas, and Sattva means the essence and character of the good dharma. Bodhisattvas are those who always have the mind to help every being to cross the stream of birth and death. A Bodhisattva is a conscious being of or for the great intelligence, or enlightenment. The Bodhisattva seeks supreme enlightenment not for himself alone but for all sentient beings. A Bodhisattva is a Mahayanist, whether monk or layman, above is to seek Buddhahood, below is to save sentient beings (he seeks enlightenment to enlighten others). A Bodhisattva is one who makes the six paramitas (lục độ) their field of sacrificial saving work and of enlightenment. The objective is salvation of all beings. Four infinite characteristics of a bodhisattva are kindness (từ), pity (bi), joy (hỷ), self-sacrifice (xả). A person, either a monk, a nun, a layman or a laywoman, who is in a position to attain Nirvana as a Sravaka or a Pratyekabuddha, but out of great compassion for the world, he or she renounces it and goes on suffering in samsara for the sake of others. He or she perfects himself or herself during an incalculable period of time and finally realizes and becomes a Samyaksambuddha, a fully enlightened Buddha. He or she discovers the Truth and declares it to the world. His or her capacity for service to others is unlimited. Bodhisattva has in him Bodhicitta and the inflexible resolve. There are two aspects of Bodhicitta: Transcendental wisdom (Prajna) and universal love (Karuna). The inflexible resolve means the resolve to save all sentient beings. A Bodhisattva is one who has the essence or potentiality of transcendental wisdom or supreme enlightenment, who is on the way to the attainment of transcendental wisdom. He is a potential Buddha. In his self-mastery, wisdom, and compassion, a Bodhisattva represents a high stage of Buddhahood, but he is not yet a supremely enlightened, fully perfect Buddha. His career lasts for aeons of births in each of which he prepares himself for final Buddhahood by the practice of the six perfections (paramitas) and the stages of moral and spiritual discipline (dasabhumi) and lives a life of heroic struggle and unremitting self-sacrifice for the good of all sentient beings. Bodhisattva is an enlightening being who, defering his own full Buddhahood, dedicates himself to helping others attain liberation. In his self-mastery, wisdom, and compassion a Bodhisattva represents a high stage of Buddhahood, but he is not yet a supreme enlightened, fully perfected Buddha. According to the Mahayana schools, the bodhisattvas are beings who deny themselves final Nirvana until, accomplishing their vows, they have first saved all the living. An enlightened being who, deferring his own full Buddhahood, dedicates himself to helping others attain liberation. Besides, the Bodhisattva regards all beings as himself ought not to eat meat.

292. Four Saints

Four Saints or four kinds of holy men in Buddhist tradition. First, Sound Hearers, direct disciples of the Buddha. Second, Pratyeka buddhas, or Individual Illuminates, or the Independently awakened; they are those enlightened to conditions; a Buddha for himself, not teaching others. Third, Bodhisattvas, or Enlightened Beings; they are those who have the state of bodhi, or a would-be-Buddha. Fourth, a Buddhas, or one who has attained the supreme right and balanced state of bodhi—One who turns the wonderful Dharma-wheel. A Buddha is not inside the circle of ten realms, but as he advents among men to preach his doctrine he is now partially included in the “Four Saints.”.

The four rewards, or four degrees of saintliness in Theravada Buddhism. The first three stages requiring study which include the stream-enterer, the once-returner, and the non-returner. The fourth stage is no longer learning or the fruit of Arahant. The first stage is Srota-apanna (Sotapatti–p), or the path of stream-entry, or the fruit of stream-entry, or stream-enterer. This is the first fruit of “Stream Winner”, one who has entered the stream. The position of the way of seeing. He still has to undergo seven instances of birth and death. This is the beginning or entering into which follows after one’s clear perception of the Four Noble Truths. The second fruit is Sakrdagamin (Sakadagami–p), or the path of once-returner. The state of returning only once again, or once more to arrive, or be born. One who is still subject to “One-return.” The position of the way of cultivation. He still has to undergo “one birth” in the heavens or “once return” among people. The second grade of arahatship involving only one rebirth. This is the fruit of one who has subjugated lust, hatred and delusion. The third fruit is Anagami, or the path of non-returner. The state which is not subject to return. One who is not subject to returning. The position of the Way of Cultivation. He no longer has to undergo birth and death in the Desire realm. This is the fruit of those who have conquered their own self. The fourth stage is no longer learning, or the fruit of Arahant (Arahatta–p), or the path of Arahantship. This is the final stage of sainthood (Worthy of offerings) in which all fetters and hindrances are severed and taints rooted out. The position of the Way of Cultivation without need of study and practice. He no longer has to undergo birth and death. Arahant is he who has attained the highest end of the Buddhist life. After his death he attains Parinirvana. The highest rank attained by Sravakas. An Arhat is a Buddhist saint who has attained liberation from the cycle of Birth and Death, generally through living a monastic life in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings. This is the supreme goal of Theravada practice, as contrasted with Bodhisattvahood in Mahayana practice.

According to Great Master Yin-Kuang from the Pure Land’s aspects, the four degrees of Hinayanist saintliness include the Srotapanna Enlightenment, Sakadagami Enlightenment, Anagami Enlightenment, and Arahat Enlightenment. The first fruit of Srotapanna Enlightenment. This is the clear perception and knowledge of the enlightened beings at this level is limited to a World System, which includes the six unwholesome paths, four great continents, Sumeru Mountain, six Heavens of Desires, First Dhyana Heaven. The second fruit of Sakadagami Enlightenment (Sakadagamin–p). This is the perception and knowledge of these beings are limited to a Small World System, consisting of 1,000 World Systems. An enlightened being in the second stage towards Arhatship, who has realized the Four Noble Truths and has eradicated a great protion of defilements. The best known example is the Bodhisattva Maitrya. He will return to the human world for only one more rebirth before he reaches full realization of Arhatship. An enlightened being who has realized the Four Noble Truths and has eradicated a great portion of defilements. He will return to the human world for only one more rebirth before he reaches full realization of Arhatship. The third fruit of Anagami Enlightenment. This is the perception and knowledge of these beings include a Medium World System, consisting of 1,000 Small World Systems. The position of the Way of Cultivation. He no longer has to undergo birth and death in the Desire realm. The position of the Way of Cultivation. He no longer has to undergo birth and death in the Desire realm. Anagamin is one of the four stages in Hinayana sanctity. According to Theravada Buddhism, anagamin is a person is free from the first five fetters of believing ego, doubt, clinging to rites and rules, sensual appetite, and resentment (who eliminated the first five fetters (samyojana): clinging to the idea of self, doubt, clinging to rituals and rules, sexual desire, and resentment). One who is never again reborn in this world. In his or her next life, such a person will be reborn in one of the five “pure abodes”. (suddhavasa) and will become an Arhat there. Non (never)-returner are those who are free from the first five fetters of believing ego, doubt, clinging to rites and rules, sensual appetite, and resentment. One who is never again reborn in this world. Never Returner is the third of the four stages on the Path, the state which is not subject to returning. The Anagami does not return to the earth after his death, but is reborn in the highest formless heaven and there attains arhatship. The fourth fruit of Arahat Enlightenment. This is the perception and knowledge of these beings encompass a Great World System, consisting of 1,000 Medium World Systems or one billion World Systems. They are able to know clearly and perfectly 84,000 kalpas in the past and 84,000 kalpas into the future. Beyond that, they cannot fully perceive.

293. Arhats

Arhat literally means “foe destroyer,” or “worthy of respect.” In early Indian Buddhism, the arhat was the most respected figure in the Buddhist community, for arhat was the one who had attained nirvana, who had servered affliction and would not be reborn into the world of suffering. According to the Theravada School, Arhat is the highest rank of attainment in Theravada Buddhism. Araht is one who has cut off all afflictions and reached the stage of “Nothing left to learn.” This is the highest stage of the four kinds of holy phalas in Hinayana Buddhism. And it has been using as one of the Buddha’s ten epithets However, in most recent Mahayana Buddhist writings, Mahayana teachers imply arhats, along with the pratyekabuddhas as low practice. They disparage the Arhats’s lower vehicle practices for being self-centered and incomplete in the wisdom of emptiness. Arhat ia one who has overcome all afflictions. Arhat is one who has done what needs be done, and attained enlightenment and is no longer subject to death and rebirth. A sravaka who has attained the highest rank. Arahant represents the example of a virtually pure superhuman teacher. So, he is an object of veneration and a merit-field which other Buddhist should follow to cultivate. Some people consider Arahant’s ideal as low, compared to the Bodhisattva ideal; however, devoted Buddhists should always remember that both of them are on the same level, but each ideal has its own special meaning. Arhat is one of the fruitions of the path of cultivation. One who attains the fruit of Arhat, or fourth stage of Sainthood, and is no more reborn anywhere. After his death he attains Parinirvana. The highest rank attained by Sravakas. An Arhat is a Buddhist saint who has attained liberation from the cycle of Birth and Death, generally through living a monastic life in accordance with the Buddha’s teachings. This is the supreme goal of Theravada practice, as contrasted with Bodhisattvahood in Mahayana practice. No longer learning (Asaiksa) or beyond learning stage refers to the stage of Arhatship in which no more learning or striving for religious achievement is needed (when one reaches this stage) because he has cut off all illusions and has attained enlightenment. The state of arhatship, the fourth of the sravaka stages; the preceding three stages requiring study; there are nine grades of arhats who have completed their course of learning.

A Pali term for “Worthy One.” The term ‘Arahanta’ is composed of two parts: Ari and hanta. Ari means enemies or defilements. Hanta means killing or destroying. So, an Arahant is a man who killed or destroyed all defilements like lust, hatred, and delusion, etc. This is an ideal phala of Theravada Buddhism; a person who has extinguished all defilements (asrava) and afflictions (klesa) so thoroughly that they will not reappear in the future. At death, the arhat enters Nirvana, and will not be reborn again. Although arhats are commonly castigated in Mahayana literature for pursuing a “selfish” goal of personal nirvana, they are also said to be worthy of respect and to have attained a higher level of spiritual development. The figure of the lo-han (arhat) became widely popular in East Asia, particularly in Ch’an, which emphasized personal striving for liberation. The earliest known representations of the arhat in China date to the seventh century, and the arhat motif became widespread in the ninth and tenth centuries. Today groups of 500 arhat figures are often seen in Ch’an monasteries, and some larger complexes have a separate “arhat hall.” It should also be mentioned that the term “arhat” is also applied to Buddhas, because they too have eliminated all defilements and enter nirvana at death. In early Buddhism, “Arahant” denotes a person who has gained insight intot the true nature of things and the Buddha was the first Arahant. After the first conversion, five brothers of Kondanna also became Arahantas. According to the Pali Nikayas such as Samyutta Nikaya, Anguttara Nikaya, and Majjhima Nikaya, Arahantas are those who comprehend the formula of the twelve causes (nidanas), had eradicated the three taints or affluences (asravas), practiced the seven factors of enlightenment (sambojjhanga), got rid of the five hindrances (nivaranas), freed himself from the three roots of evil, and ten fetters. He practiced self-restraint and concentration, and acquired various supernatural powers, and awakened the nature of the misery of samsara. He practice four dhyanas, eight attainments. He obtained eight kinds of super knowledge, threefold knowledge, resulted in the liberation in the end. This freedom made him an Arahant who destroyed the fetter of rebirth in the cycle of samsara and enjoyed himself in Nirvana, and was worthy of being revered in this world.

According to the Sthaviras, Arhats are perfect beings; but according to the Mahasanghikas, Arhats are not perfect, they are still troubled by doubts and are ignorant of many things. Thus, Mahayana Buddhism advises Buddhists not to hold up Arhats as ideals. Rather those should be emulated as ideals who during aeons of self-sacrifice and continuous struggle to save sentient beings and to attain Buddhahood. In the Book of Kindred Sayings, the Buddha does not make any statement differentiating between Himself and an Arahant: “The Tathagata, Brethren, who being Arahant, is fully enlightened, he it is who doth cause a way to arise which had not arisen before; who doth bring about a way not brought about before; who doth proclaim a way not proclaimed before; who is the knower of a way, who understands a way, who is skilled in a way. And now, brethren, his disciples are way-farers who follow after him. That, brethren, is the distinction, the specific feature which distinguishes the Tathagat who, being Arahant, is fully enlightened, from the brother who is free be insight.” According to the “Buddhist Images of Human Perfection”, Nathan Katz showed that: “The Arahant is said to be equal to the Buddha in terms of spiritual attainment, as they have both completely overcome the asava. According the the Milindapanha, Arahants outshining all other Bhiksus, overwhelming them in glory and splendor, because they are emancipted in heart. Arahantship is called the jewel of emancipation.

Arhat still has three meanings: Worthy of offerings, Slayer of thieves, and Patience with the nonproduction of dharmas. First, Worthy of offerings. One who is worthy of offerings, or worthy of worship or respect from humans and gods, one of the ten titles of a Tathagata. It is said that if you make offerings to an Arahan, you thereby attain limitless and boundless blessings. There is no way to calculate how manyWorthy of offerings, worthy of worship or respect from humans and gods, one of the ten titles of a Tathagata. It is said that if you make offerings to an Arahan, you thereby attain limitless and boundless blessings. There is no way to calculate how many. Second, slayer of thieves, or killer of the demons of ignorance, or slayer of the enemy. The thieves here are not external thieves, but the thieves within yourself: the thieves of ignorance, the thieves of afflictions, the thieves of greed, hatred, pride, doubt, wrong views, killing, stealing, lying, and so on. They are unknown to you, but they quietly rob all your virtues. Third, patience with the nonproduction of dharmas. They have attained the patience with the nonproduction of dharmas. They do not have to be reborn, because they have destroyed all the karma of reincarnationThey have attained the patience with the nonproduction of dharmas. They do not have to be reborn, because they have destroyed all the karma of reincarnation. Those are also called “Great Arhats”. At the time of the Buddha, Great Arhats are great beings belonging to the Dharmakaya, i.e. Great Bodhisattvas, who expendiently take the appearance of monastic disciples of the Buddha. They have realized the inconceivable reality of the Buddha Dharma, and so they are called “great”. They accompanied the Buddha as He turned the Wheel of the Dharma, bringing benefits to all the realms of humans and gods, and so they were well known to all (in all Buddhist Sutras, 1,250 bhiksus were always mentioned).

According to the Encyclopedia of Buddhism, the word ‘Arahanta’ is derived from the root ‘Arh’, to deserve, to be worthy, to be fit, and is used to denote a person who has achieved the goal of religious life in Theravada Buddhism. Arahanta is composed of two parts’Ari’ and ‘Hanta’. ‘Ari’ means enemies or defilements. ‘Hanta’ means killing or destroying. So, an Arahant is a man who killed or destroyed all defilements like lust, hatred and ignorance. I.B. Hornor in “The Early Buddhist Theory of Man Perfected” gives us the following four forms of the nouns: araha, arahat, arahanta, and arahan. In early Buddhism, the term denotes a person who has gained insight into true nature of things, and the Buddha was the first Arahant. After the first conversion, five brothers of Kondanna also became Arahants. The Arahants are described as Buddhanubuddha, i.e., those who attained enlightenment after the fully Enlightened One. Then, as time passed, the conception of Arahantship was gradually widened and elaborated by the Buddha and his successors. Thus, an Arahant who was also supposed to comprehend the formula of the twelve nidanas, had eradicated the three asravas, practiced the seven factors of enlightement, got rid of the five hindrances, freed himself from the three roots of evil, ten fetters of belief. He practiced self-restraint and concentration, and acquired various supernatural power, and awakened the nature of the misery of samsara. He practiced the Four meditations, four ecstatic attainments and the supreme condition of trance and obtained the six kinds of super knowledge, threefold knowledge, etc, resulted in the liberation in the end. This freedom made him an Arahant who destroyed the fetter of rebirth in the cycle of samsara and enjoyed himself in Nibbana, and was worthy of being revered in this world. In the Pasadika Sutta, the Buddha reminded us the following Arahant formula: “The brother who is an Arahant in whom the intoxicants are destroyed, who has done his task, who has laid down his burden, who has attained salvation, who has utterly destroyed the fetters of rebirth, who is emancipated by true dharmas. The dicipline of a Buddhist is aimed at the attainment of Arahantship. In other words, Arahant is an ideal man or sage at the highest of spiritual development.

According to the view of Theravada Buddhism, during the life of the Buddha, many of his disciples attained enlightenment in his presence. They fully eradicated the fires of greed, hatred and delusion and, having attained Nirvana, were released from samsara, the endless cycle of rebirth. These “Worthy Ones” (Arhats) form part of the Noble Sangha (in which Buddhists take refuge), along with the Buddha and the Dharma, and represent the ideal of the Theravada tradition. Because they received the teaching as disciples, rather than discovering it for themselves, they are not “Perfect Buddhas.” Famous Arhats include Sariputra, known for his wisdom and ability to teach; Mogallana, renowned for his mental and meditational power; and Ananda, the Buddha’s attendant, who was recognized for his devotion and supernatural memory in reciting the Buddha’s teaching at the First Council. Ananda is also known for his role in establishing the first Buddhist order of nuns. The position of the Arhat, the Consummate One, is very clear. When a person totally eradicates the lust, hatred, and delusion, that leads to becoming, he is liberated from the shackles of samsara, from repeated existence. He is free in the full sense of the word. He no longer has any quality which will cause him to be reborn as a living being, because he has realized Nibbana, the entire cessation of continuity and becoming (bhava-nirodha); he has transcended common or worldly activities and has raised himself to a state above the world while yet living in the world: his actions are issueless, are karmically ineffective, for they are not motivated by the lust, hatred and delusion, by the mental defilements (kilesa). He is immune to all evil, to all defilements of the heart. In him, there are no latent or underlying tendencies (anusaya); he is beyond good and evil, he has given up both good and bad; he is not worried by the past, the future, nor even the present. He clings to nothing in the world and so is not troubled. He is not perturbed by the vicissitudes of life. His mind is unshaken by contact with worldly contingencies; he is sorrowless, taintless and secure. While the Mahayanists always maintained that an Arhat had not completely shaken off all attachment to ‘I’ and ‘mine.’ He set out to obtain Nirvana for himself, and he won Nirvana for himself, but others were left out of it. In this way, the Arhat could be said to make a difference between himself and others, and thereby to retain, by implication, some notion of himself as different from others, thus showing his inability to realize the truth of ‘Not-self’ to the full. Mahayana Buddhism compared the Arhat unfavorably with the Bodhisattva, and it claimed that all should emulate the Bodhisattva and not the Arhat.

In the Dharmapada Sutra, the Buddha taught: “There is no more suffering for him who has completed the journey; he who is sorrowless and wholly free from everything; who has destroyed all fetters (Dharmapada 90). The mindful exert themselves, they do not enjoy in an abode; like swans who have left their pools without any regret (Dharmapada 91). Arhats for whom there is no accumulation, who reflect well over their food, who have perceived void, signless and deliverance, and their path is like that of birds in the air which cannot be traced (Dharmapada 92)Arhats for whom there is no accumulation, who reflect well over their food, who have perceived void, signless and deliverance, and their path is like that of birds in the air which cannot be traced (Dharmapada 92). Arhats whose afflictions are destroyed, who are not attached to food, who have perceived void, signless and deliverance, and their path is like that of birds in the air which cannot be traced (Dharmapada 93). The gods even pay homage to Arhats whose senses are subdued, like steeds well-trained by a charioteer, those whose pride and afflictions are destroyed (Dharmapada 94). Like the earth, Arhats who are balanced and well-disciplined, resent not. He is like a pool without mud; no new births are in store for him (Dharmapada 95). Those Arhats whose mind is calm, whose speech and deed are calm. They have also obtained right knowing, they have thus become quiet men (Dharmapada 96). The man who is not credulous, but knows the uncreated, who has cut off all links and retributions, and renounces all desires. He is indeed a supreme man (Dharmapada 97). In a village or in a forest, in a valley or on the hills, on the sea or on the dry land, wherever Arhats dwell, that place is delightful (Dharmapada 98). For Arhats, delightful are the forests, where common people find no delight. There the passionless will rejoice, for they seek no desires nor sensual pleasures (Dharmapada 99). According to the Sutra In Forty-Two Sections, Chapter 1, the Buddha said: “Always observe the 250 precepts; enter into and abide in purity by practicing the Four Noble Truths, which accomplish Arahantship. Arahants can fly and transform themselves. They have a lifespan of vast aeons and wherever they dwell they can move earth and heaven. One who achieves (certifies) Arahantship severes love and desire in the same manner as severing the four limbs; one is never able to use them again.”

294. Five Pure-Dwelling Heavens

In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, the Buddha told Ananda about the Five Pure Dwelling Heavens as follows: “Ananda! Beyond the four Dhyana Heavens, are the five pure dwelling heavens or heavens of no return. For those who have completely cut off the nine categories of habits in the lower realms, neither suffering nor bliss exist, and there is no regression to the lower levels. All whose minds have achieved this renunciation dwell in these heavens together. First, No Affliction Heaven, those who have put an end to suffering and bliss and who do not get involved in the contention between such thoughts are among those in the Heaven of No Affliction. Second, No Heat Heaven, those who isolate their practice, whether in movement or in restraint, investigating the baselessness of that involvement, are among those in the Heaven of No Heat. Third, The Good View Heaven, those whose vision is wonderfully perfect and clear, view the realms of the ten directions as free of defiling appearances and devoid of all dirt and filth. They are among those in the Heaven of Good View. Fourth, the Good Manifestation Heaven, those whose subtle vision manifests as all their obstructions are refined away are among those in the Heaven of Good Manifestation. Fifth, the Ultimate Form Heaven, those who reach the ultimately subtle level come to the end of the nature of form and emptiness and enter into a boundless realm. They are among those in the Heaven of Ultimate Form.

295. Six Desire Heavens

Six Desire Heavens or Heavens of Desires (they are still in the region of sexual desire). The six Desire Heavens are the heavens of the Desire Realm. The Desire Realm, the Form Realm and the Formless Realm are called the Three Realms. According to Buddhism, we are under the Heaven of the Four Kings, which is one of the six Desire Heavens. The heaven which we can see directly is the Heaven of the Four Kings, ruled by the Four Great Heavenly Kings. This Heaven is located halfway up Mount Meru. These are Heavens in which the Heavenly beings are still attached to intimate relations from low to high. Owing to the cultivation of the five precepts and ten good deeds, beings earn the blessing of being born in this Heaven. However, these are good roots which have outflows. So it is difficult for them to end the cycle of birth and death. In the Surangama, the Buddha reminded Ananda about the six heavens, although they have transcended the physical in these six heavens, the traces of their minds still become involved. First, the heaven of the four kings (Catur-maha-rajakayika skt). The Heaven of the four Kings. It is described as half-way up Mount Sumeru. In the Surangama Sutra, book Eight, the Buddha explained to Ananda about the Heaven of the four kings as follows: “Ananda! There are many people in the world who do not seek what is eternal and who cannot renounce the kindness and love they feel for their wives, but they have no interest in deviant sexual activity and so develop a purity and produce light. When their life ends, they draw near the sun and moon and are among those born in the heaven of the four kings. Second, Trayastrimsha, or the Trayastrimsha Heaven. It is described as at the summit of Mount Sumeru. This Heaven is in the middle of eight heavens in its east, eight heavens in its west, eight heavens in its south, and eight heavens in its north, making thirty-two heavens surrounding it. It is said that this is the second of the desire-heavens, the heaven of Indra, on the summit of Meru. It is the Svarga of Hindu mythology, situated at the top of Meru with thirty-two deva-cities, eight on each side; a central city is Sudarsana, or Amaravati, where Indra, with 1,000 heads and eyes and four arms, lives in his palace called Vaijayanta, and revels in numberless sensual pleasures together with his wife Saci and with 119,000 concubines. There he receives the monthly reports of the four Maharajas as to the good and evil in the world.” The average lifespan of gods in this heaven is 30,000,000 years. It is said that Sakyamuni Buddha has visited there for three months during the seventh year after his awakening in order to preach the Abhidharma to his mother. This is the second level heaven of six heavens of desire, also called Heaven of Thirty-Three. The palace of Trayastrimsa Heaven, one of the ancient gods of India, the god of the sky who fights the demons with his vijra, or thunderbolt. He is inferior to the Trimurti, Brahma, Visnu, and Siva, having taken the place of Varuna, or sky. Buddhism adopted him as its defender, though, like all the gods, he is considered inferior to a Buddha or any who have attained bodhi. His wife is Indrani. According to Bhikkhu Bodhi in Abhidhamma, Tavatimsa is so named because, according to legend, a group of thirty-three noble-minded men who dedicated their lives to the welfare of others were reborn here as the presiding deity and this thirty-two assistants. The chief of this realm is Sakka, also known as Indra, who resides in the Vejayanta Palace in the realm’s capital city, Sudassana. In the Surangama Sutra, the Buddha said, “Those whose sexual love for their wives is slight, but who have not yet obtained the entire flavor of dwelling in purity, transcend the light of sun and moon at the end of their lives, and reside at the summit of the human realm. They are among those born in the Tryastrimsha Heaven.” The rest four Heavens are located between Mount Sumeru and the Brahmalokas. Third, the heavens of Suyama. Among them, there is a heaven called “Extreme Happy Heaven”. Beings in the Suyama Heaven are extremely happy, and they sing songs from morning to night. They are happy in the six periods of the day and night, that is why people call “Suyama Heaven” the Heaven of Time Period, for every time period is joyful. In the Surangama Sutra, the Buddha said: “Those who become temporarily involved when they meet with desire but who forget about it when it is finished, and who, while in the human realm, are active less and quiet more, abide at the end of their lives in light and emptiness where the illumination of sun and moon does not reach. These beings have their own light, and they are among those born in the Suyama Heaven.” The Fourth Heaven is the Tushita Heaven. Tushita means “Blissfully Content.” Beings in this Heaven are constantly happy and satisfied. Since they know to be content, they are always happy. From morning to night, they have no cares nor worries; no afflictions nor troubles. That is why this Heaven is also called the Heaven of Contentment. In the Surangama Sutra, the Buddha said: “Those who are quiet all the time, but who are not yet able to resist when stimulated by contact, ascend at the end of their lives to a subtle and ethereal place; they will not be drawn into the lower realms. The destruction of the realms of humans and gods and the obliteration of kalpas by the three disasters will not reach them, for they are among those born in the Tushita Heaven.” The Fifth Heaven is the Transformation of Bliss Heaven (Nirmanarati—Joy-born heaven). Beings in this Heaven can obtain happiness by transformation. When they think about clothing, clothing appears. When they think about food, food appears. Freely performing transformations, they are extremely blissful. The fifth of the six desire-heaven, 640,000 yojanas above Meru; it is next above the Tusita (fourth devaloka). A day there is equal 800 human years; life lasts 8,000 years; its inhabitants are eight yojanas in height, and ligh-emitting; mutual smiling produces impregnation and children are born on the knees by metamorphosis, at birth equal in development to human children of twelve. In the Surangama Sutra, the Buddha said: “Those who are devoid of desire, but who will engage in it for the sake of their partner, even though the flavor of doing so is like the flavor of chewing wax, are born at the end of their lives in a place of transcending transformations. They are among those born in the Heaven of Bliss by Transformation.” The sixth Heaven is the Heaven of Transformation of Others’ Bliss (Parinimmita-vasavati p). Also called the Comfort Gained From The Transformation of Others’ Bliss. Beings in this Heaven have no happiness of their own, so they have to take the bliss of other gods and transform it into their own. Why do they do this? It is because they obey no rules. They are just like bandits in the human realm who seize the wealth and possessions of other people for themselves, not caring whether other live or die. In the Surangama Sutra, the Buddha said: “Those who have no kind of worldly thoughts while doing what worldly people do, who are lucid and beyond such activity while involved in it, are capable at the end of their lives of entirely transcending states where transformations may be present and may be lacking. They are among those born in the Heaven of the Comfort from others’ transformations.”

296. Twelve Yaksha Generals

According to the Bhaisajyaguru vaidurya Prabhasa Sutra, there are twelve Yaksha generals; they are not really devas, but they are higher than human beings. Each of the twelve Yaksha General has an army of seven thousand Yakshas. The unanimously pledged to the Buddha. “Lokajyestha, by the Buddha’s power, we have learned of the name Lokajyestha Bhaisajyaguru vaidurya Prabhasa Tathagata, we have no more fear or evil rebirth. We all sincerely take refuge in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha for the rest of our natural lives. We will serve all beings, promote their benefit and comfort. Any town or village, country or forest, wherever this Sutra is preached, and wherever the name Bhaisajyaguru Vaidurya Prabhasa Tathagata is venerated, we and our army will protect the faithful and rescue them from calamity. All their wishes will be fulfilled. Those in sickness and danger should recite this sutra. They should take a five colored skein, and tie it into knots to form our names. They can untie the knots when the wishes are fulfilled. Twelve Yaksha Generals include General Kumbhira, General Vajra, General Mihira, General Andira, General Majira, General Shandira, General Indra, General Pajra, General Makuram, General Sindura, General Catura, and General Vikarala.

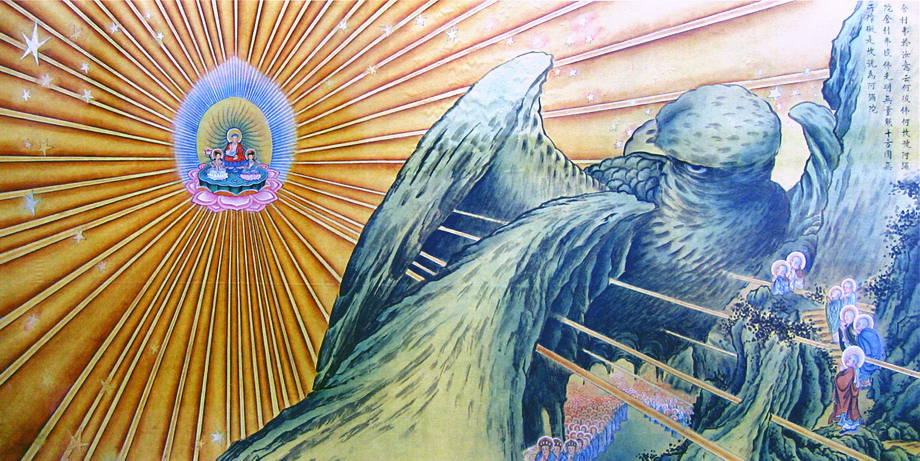

297. Eight Classes of Divinities

Devas, nagas and others of the eight classes—The eight groups of demon followers which existed in ancient Indian legends; however, they were often utilized in Buddhist sutras to suggest the diversity of the Buddha’s audiences. Eight classes of divinities, or eight kinds of gods and demi-gods. These are various classes of non-human beings that are regarded as protectors of Buddhist Dharma and Buddhism as part of the audience attending the Buddha’s sermons. Divinities are not ordinarily visible to human eyes; however, their subtle body can be clearly seen with higher spiritual power. First, devas, gods, or angels in the Heavens. Second, dragons or heavenly dragons. Dragons are regarded as beneficent, bringing the rains. As dragon it represents the chief of the scaly reptiles; it can disappear or manifest, increase or decrease, lengthen or shrink at will. It can mount in the sky and in water, and enter the earth. In spring it mounts in the sky and in winter enters the earth. Dragon or a beneficent half-divine being (serpent or serpent demon). They supposed to have a human face with serpent-like lower extremities. With Buddhism, they are also represented as ordinary men. Snakes and Dragons are symbols of initiates of the wisdom, especially in India the Nagas or Serpent Kings are symbols of initiates of the Wisdom. Dragons are also guarding the heavens. Dragơns control rivers and lakes, and hibernate in the deep. Naga and Mahanaga are titles of those freed from reincarnation, because of his powers, or because like the dragon he soared above earthly desires and ties. Besides, Naga and Mahagana are titles of a Buddha. “Naga” is a Sanskrit term for “Serpent-like beings.” A kind of being with bodies of snakes and human heads, said to inhabit in the waters or the city of Bhoga-vati under the waters. They are said to be endowed with miraculous powers and to have capricious natures. According to Madhyamaka mythology, they played a key role in the transmission of the “Perfection of Wisdom” (Prajna-Paramita) texts. Fearing that they would be misunderstood, the Buddha reportedly gave the texts to the nagas for safekeeping until the birth of someone who was able to interpret them correctly. This was Nagarjuna (150-250), who is said to have magically flown to the nagas city and received the hidden books. The story is apparently intended to explain only the chronological discrepancy between the death of the Buddha and the appearance of these texts. A naga maiden, daughter of sagar-nagaraja, the dragon king at the bottom of the ocean; she is presented in the Lotus sutra, though a female and only eight years old, as instantly becoming a Buddha, under the tuition of Manjusri. It is incredible that a girl as the daughter of the Dragon King should become perfectly enlightened in a moment, but the Buddha already certified that, and she already revealed the teaching of the Great Vehicle to deliver creatures from suffering. At that time, the saha world of Bodhisattvas, Sravakas, Pratyeka-buddhas, gods, and human and non-human beings, beholding the dragon’s daughter become a Buddha and universally preach the Law to the gods. On witnessing her preach the Law and become a Buddha, the whole assembly were aroused to realization and attain the stage of “never sliding back into mortality,” and they also received their prediction of attainment of Buddhahood. Third, Yaksas, extremely fast demons that guard Heaven’s Gates, sometimes associated with the Tusita Heaven, but usually located on the human plane (realm). This is a class of beings who live in the earth, air, lower heavens, and forests. They are endowed with supernatural powers and are sometimes beneficent, but sometimes malignant and violent. In Buddhism, yaksas are supernatural beings, usually good without violent (divine in nature and possess supernatural powers), frequently mentioned in Buddhist sutras. They are often said to be present at the preaching of Buddhist sutras. This is a swift (extremely fast), powerful kind of ghost or demon, which is usually harmful, but in some cases acts as a protector of the Dharma or guardians of Heaven’s gates. Some defines Yaksa as a divine being of great power, or non-human who ranks between man and Gandharva (gandhabba). In some cases, other yaksas, mainly the females, called yaksini, are wild demonic beings who live in solitary places and are hostile toward people, particularly those who lead a spiritual life, devourers of human flesh. They often disturb the quietness in the temple and the meditation of monks and nuns by making loud noise. There are also some extremely fast demons who guard Heaven’s Gates. Fourth, Gandharvas, musician Angels for the Cakra Heaven Kings. “Fragrance-devouring celestial musicians.” The celestial gandharva is a deity who knows and reveals the secrets of the celestial and divine truth. Demigods who are also heavenly singers and musicians who took part in the orchestra at the banquets of the gods. They follow after women and are desirous of intercourse with them; they are also feared as evil beings. Gandharva or Gandharva Kayikas, spirits on Gandha-mandala (the fragrant or inscent mountains), so called because the Gandharvas do not drink wine or eat meat, but feed on inscense or fragrance and give off fragrant odours. As musicians of Indra, or in the retinue of Dhrtarastra, they are said to be the same as, or similar to, the Kinnaras. They are Dhrtarastra, associated with soma, the moon, and with medicine. They cause ecstasy, are erotic, and the patrons of marriageable girls; the Apsaras are their wives, and both are patrons of dicers. They live in the region of the air and the heavenly waters and are especially associated with the Caturmaharajika realm. Fifth, asuras, war gods, or evil spirits which live on the slopes of Mount Meru, below the lowest heavenly sphere, that of the four Guardian Kings. The sixth class of divinities is Garudas. “Garudas” is a Sanskrit term for “Devourer,” or “king of bird,” figures of mythical birds with human heads, heavenly birds with great golden wing spans of approximately 3,360,000 miles, the traditional enemies of Nagas. Dragon-devouring bird, the vehicle of Vishnu (this is a golden winged bird, the vehicles of Visnu, lords of the winged race and natural enemies of Nagas). This is the king of birds, with golden wings, companion of Visnu. Garuda-raja or king of birds are used to compare with the great people, while the crow are used to compare with the wicked people. In Buddhism, the king of birds is a symbol of the Buddha. The seventh class of divinities is Kinnaras, heavenly beings with human bodies and animal heads (half-horse, half-men). A being resembling but not a human being. A being having the appearance of humans but possessing parts of animals. A kind of mythical celestial musician. It has a horse-like head with one horn, and a body like that of human. The males sing and the females dance. They are described as “men yet not men.” They are one of the eight classes of heavenly musicians; they are also described as horned, as having crystal lutes, the females singing and dancing, and as ranking below gandharvas. Kinnaras are mythical beings (heavenly beings), or musicians of Kuvera, with a human figure and the head of a horse or with a horse’s body and the head of a man. They are described as “men yet not men.” They are one of the eight classes of heavenly musicians; they are also described as horned, as having crystal lutes, the females singing and dancing, and as ranking below gandharvas. The eighth class of divinities is Mahoraga, one of the eight classes of supernatural beings in the Lotus Sutra or eight Vajra Deities. Serpent or Snake gods with body length over 100 miles. This is a class of demons in Buddhism shaped like a boa or great snake. Mahoragas are depicted to be large-bellied creatures shaped like boas who are said to be lords of the soil. They are mentioned among the audience of a number of Mahayana sutras.

298. Four Dhyana Heavens

The first heaven is the Pathamajjhanabhumi. This is the first region, as large as the whole universe. The inhabitants in this region are without gustatory (tasting) or olfactory (smelling) organs, not needing food, but possess the other four of the six organs. Heaven beings in this Heaven are free from all sexual desires; nevertheless, they still have other desires. This is the ground of joy of separation from production. The first dhyana has one world with one moon, one meru, four continents and six devalokas. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, the Buddha told Ananda about the Pathamajjhanabhumi as follows: “Ananda! Those who flow to these three superior levels in the Pathamajjhanabhumi (first dhyana) will not be oppressed by any suffering or affliction. Although they have not developed proper samadhi, their minds are pure to the point that they are not moved by outflows.” Sublevels of the First Dhyana Heaven include the first heaven is the realm of Brahma’ ministers. The assembly of Brahmadevas, belonging to the retinue of Brahma; the first Brahmaloka; the first region of the first dhyana heaven of form. According to the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, all those in the world who cultivate their minds but do not avail themselves of dhyana and so have no wisdom, can only control their bodies so as to not engage in sexual desire. Whether walking or sitting, or in their thoughts, they are totally devoid of it. Since they do not give rise to defiling love, they do not remain in the realm of desire. These people can, in response to their thought, take on bodies of Brahma beings. They are among those in the Heaven of Multitudes of Brahma. The second heaven is the realm of Brahma’s retinue. This is the second Brahmaloka; the second region of the first dhyana heaven of form. The ministers, or assistants of Brahma. According to the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those whose hearts of desire have already been cast aside, the mind apart from desire manifests. They have a fond regard for the rules of discipline and delight in being in accord with them. These people can practice the Brahma virtue at all times, and they are among those in the Heaven of the Ministers of Brahma. The third heaven is the realm of the great Brahmas. According to Eitel in the Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms, Mahabrahman is the first person of the Brahminical Trimurti, adopted by Buddhism, but placed in an inferior position, being looked upon not as Creator, but as a transitory devata whom every Buddhistic saint surpasses on obtaining bodhi. Notwithstanding this, the saddharma-pundarika calls Brahma or the father of all living beings (cha của tất cả chúng sanh). Mahabrahman is the unborn or uncreated ruler over all, especially according to Buddhism over all the heavens of form, of mortality. According to the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those whose bodies and minds are wonderfully perfect, and whose awesome deportment is not in the least deficient, are pure in the prohibitive precepts and have a thorough understanding of them as well. At all times these people can govern the Brahma Multitudes as great Brahma Lords, and they are among those in the great Brahma Heaven. According to Pali Nikayas, the first region, as large as the whole universe. In this region, practitioners attain initial and sustained thought, rapture and joy, one-pointedness of mind, impingement (touching), feeling, perception, will, thought, desire, determination, energy, mindfulness, equanimity, and attention. Also, practitioners in this region have the ability to be aloof from pleasure of senses and unskilled state of mind.

The second heaven is the second dhyana. The Dutiyajjhanabhumi is the second region, equal to a small chilio cosmos. The inhabitants in this region have ceased to require the five phisical organs, possessing only the organ of mind. This is the ground of joy of production of samadhi. The second dhyana has one thousand times the worlds of the first. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, the Buddha told Ananda about the Dutiyajjhanabhumi as follows: “Ananda! Those who flow to these three superior levels in the second dhyana will not be oppressed by worries or vaxations. Although they have not developed proper samadhi, their minds are pure to the point that they have subdued their coarser outflows.” Sublevels of the Second Dhyana Heaven include the Minor-Light Heaven. The realm of minor lustre. The fourth Brahmaloka or the first region of the second dhyana heavens. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, Those beyond the Brahma Heavensgather in and govern the Brahma beings, for their Brahma conduct is perfect and fulfilled. Unmoving and with settled minds, they produce light in profound stillness, and they are among those in the Heaven of Lesser Light. Infinite-Light Heaven, or the heaven of boundless light, the fifth of the Brahmalokas. The realm of infinite lustre. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those whose lights illumine each other in an endless dazzling blaze shine throughout the realms of the ten directions so that everything becomes like crystal. They are among those in the Heaven of Limitless Light. Light and Sound Heaven, or the Utmost Light-Purity. The realm of the radiant Brahmas. There are no sounds heard in this heaven; when the inhabitants wish to talk, a ray of pure light comes out of the mouth, which serves as speech. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those who take in and hold the light to perfection accomplish the substance of the teaching. Crating and transforming the purity into endless responses and functions, they are among those in the Light-Sound Heaven. According to Pali Nikayas, the second region, equal to a small chilio cosmos. In this region, practitioners attain inward tranquility, rapture, joy, one pointed of mind, touching, feeling, equnimity and attention. Also, practitioners in this region have the ability to annihilate initial and discursive thought.

The third heaven is the Tatiyajjhanabhumi. This is the third region, equal to a middling chiliocosmos. The inhabitants in this region still have the organ of mind are receptive of great joy—This is the ground of wonderful bliss and cessation of thought. The third has one thousand times the worlds of the second. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, the Buddha told Ananda about the third dhyana as follows: “Ananda! Those who flow to these three superior levels in the third dhyana will be replete with great compliance. Their bodies and minds are at peace, and they obtain limitless bliss. Although they have not obtained proper samadhi , the joy within the tranquility of their minds is total.” Sublevels of the Third Dhyana Heaven include Minor Purity, the first and smallest heaven (brahmaloka) in the third dhyana region of form. The realm of the Brahmas of minor aura. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, Heavenly beings for whom the perfection of light has become sound and who further open out the sound to disclose its wonder discover a subtler level of practice. They penetrate to the bliss of still extinction and are among those in the Heaven of Lesser Puirty. Boundless purity, or Infinite Purity, the second of the heaven in the third dhyana heavens of form. The realm of the Brahmas of infinite aura. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those in whom the emptiness of purity manifests are led to discover its boundlessness. Their bodies and minds experience light ease, and they accomplish the bliss of still extinction. They are among those in the Heaven of Limitless Purity. Universal Purity Deva, or the heaven of universal purity, the third of the third dhyana heavens. The realm of the Brahmas of steady aura. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those for whom the world, the body, and the mind are all perfectly pure have accomplished the virtue of purity, and a superior level emerges. They return to the bliss of still extinction, and they are among those in the Heaven of Pervasive Purity. According to Pali Nikayas, the third region, equal to a middling chiliocosmoasIn this region, practitioners attain equnimity, joy, mindfulness, clear consciousness, one-pointedness, impingement (touching), feeling, perception, will, thought, desire, determination, energy, mindfulness, equanimity, and attention. Also, practitioners in this region have the ability to fade out of rapture, dwelling with equanimity.

The fourth heaven is the fourth dhyana heaven. The fourth region, equal to a great chiliocosmos. The inhabitants in this region still have mind. This is the ground of purity and renunciation of thought. The fourth dhyana has one thousand times those of the third. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, the Buddha told Ananda about the fourth dhyana as follows: “Ananda! Those who flow to these four superior levels in the fourth dhyana will not be moved by any suffering or bliss in any world. Although this is not the unconditioned or the true ground of non-moving, because they still have the thought of obtaining something, their functioning is nonetheless quite advanced.” Sublevels of the Fourth Dhyana Heaven include Felicitous Birth heaven. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, heavenly beings whose bodies and minds are not oppressed, put an end to the cause of suffering, and realize that bliss is not permanent; that sooner or later it will come to an end. Suddenly they simultaneously renounce both thoughts of suffering and thoughts of bliss. Their coarse and heavy thoughts are extinguished, and they give rise to the nature of purity and blessing. They are among those in the Heaven of the Birth of Blessing. No-Cloud or Blessed Love Heaven. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, those whose renunciation of these thoughts is in perfect fusion gain a purity of superior understanding. Within these unimpeded blessings they obtain a wonderful compliance that extends to the bounds of the future. They are among those in the Blessed Love Heaven. Large fruitage or the realm of the Brahmas of great reward. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, from the Blessed Love Heaven there are two ways to go: the first way is the Abundant Fruit Heaven, and the second way is the No Thought Heaven. Those who extend the previous thought into limitless pure light, and who perfect and clarify their blessings and virtue, cultivate and are certified to one of these dwellings. They are among those in the Abundant Fruit Heaven. No vexations, or free of trouble, the thirteenth Brahmaloka, the fifth region of the fourth dhyana. No heat, without heat or affliction, the second of the five pure-dwelling heavens, in the fourth dhyana heaven. Beautiful to see or Good to see Heaven. Beautiful appearing or the beautiful realm. Heaven of Beautiful Presentation, the third heaven in the five pure-dwelling heavens. The highest heaven of form or the highest of the material heavens. Akanishtha literally means “not the least” or “not the smallest,” and the heaven so designated is regarded as situated at the highest end of the Rupadhatu or Rupaloka, the world of Form. According to Dr. Unrai Wogihara in Mahavyutpatti, page 306, “aka” must have been originally “agha”, and “agha” ordinarily means “evil” or “pain,” but Buddhists understood it in the sense of form, perhaps because pain is inevitable accompaniment of form. Hence the Chinese “Akanishtha” means limit or end of form. The Heaven Above Thought or No Thought Heaven. In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, from the Blessed Love Heaven there are two ways to go. Those who extend the previous thought into a dislike of both suffering and bliss, so that the intensity of their thought to renounce them continues without cease, will end up by totally renouncing the way. Their bodies and minds will become extinct; their thoughts will become like dead ashes. For five hundred aeons these beings will perpetuate the cause for production and extinction, being unable to discover the nature which is neither produced nor extinguished. During the first half of these aeons they will undergo extinction; during the second half they will experience production. They are among those in the Heaven of No Thought. Within a kalpa of destruction, the first is destroyed fifty-six times by fire, the second seven by water, the third once by wind, the fourth corresponding to a state of “absolute indifference” remains “untouched” by all the other evolutions; however, when fate comes to an end, then the fourth dhyana may come to an end too, but not sooner. According to Pali Nikayas, the fourth region, equal to a great chiliocosmos. In this region, practitioners attain equanimity, feeling that neither painful nor pleasant, impassive of mind, purification by mindfulness, one-pointedness of mind, impingement (touching), feeling, perception, will, thought, desire, determination, energy, mindfulness, equanimity, and attention.

299. Four Formless Jhanas

According to the Sangiti Sutta in the Long Discourses of the Buddha, there are four Formless Jhanas. The first formless jhana is the Sphere of Infinite Space. This is the first of the four immaterial jhanas. In this region, practitioners attain perception the plane of Infinite Either, one-pointedness of mind, and attention. Also, here practitioners, by passing entirely beyond bodily sensations, by the disappearance of all senses of resistance, and by non-attraction to the perception of diversity, seeing that space is infinite, reaches and remains in the Sphere of Infinite Space, which is beyond Perception of Material Shapes. When the mind, separated from the realm of form and matter, is exclusively directed towards infinite space, it is said to be abiding in the Akasanantya-yatanam. To reach this, a meditator who has mastered the fifth fine-material jhana based on a “kasina” object spreads out the counterpart sign of the “kasina” until it becomes immeasurable in extent. The he removes the “kasina” by attending only to the space it pervaded, contemplating it as “infinite space.” The expression “base of infinite space,” strictly speaking, refers to the concept of infinite space which serves as the object of the first immaterial-sphere consciousness. This is the state or heaven of boundless space, where the mind becomes void and vast like space. Existence in this stage may last 20,000 great kalpas. The second formless jhana is the Sphere of Infinite Consciousness. In this region, practitioners attain perception the plane of Infinite consciousness, one-pointedness of mind, impingement, feeling, equanimity,… and attention. Also, here practitioners, passing entirely beyond the Sphere of Infinite Space, seeing that consciousness is infinite, he reaches and remains in the Sphere of Infinite Consciousness, which is beyond the plane of Infinite Either. After attaining the state of the base of infinite space, meditator continues to concentrate on this state of “infinite space” until he takes as object the consciousness of the base of infinite space, and contemplates it as “infinite consciousness” until the second immaterial absorption arises, or when the mind going beyond infinite space is concentrated on the infinitude of consciousness it is said to be abiding in the Vijnananantya. This is the state or heaven of boundless knowledge. Where the powers of perception and understanding are unlimited. Existence in this stage may last 40,000 great kalpas. The third formless jhana is the Sphere of No-Thingness. In this region, practitioners attain perception the plane of Nothing, one-pointedness of mind, impingement, feeling, equanimity,… and attention. Also, here practitioners, by passing entirely beyond the Sphere of Infinite Consciousness, seeing that there is nothing, he reaches and remains in the Sphere of No-Thingness, which is beyond the plane of Infinite Consciousness. The third immaterial attainment has its object the present non-existence or voidness. Meditators must give attention to the absence of that consciousness in the second immaterial-sphere consciousness. When the mind going even beyond the realm of consciousness finds no special resting abode, it acquires the concentration called “knowing nowhere to be.” This is the state or heaven of nothing or non-existence. Where the discriminative powers of mind are subdued. Existence in this stage may last 60,000 great kalpas. The fourth formless jhana is the Sphere of Neither Perception Nor Non- Perception. This fourth and final immaterial attainment is so called because it cannot be said either to include perception or to exclude perception. The nature of this concentration is neither in the sphere of mental activities nor out of it. This is the state or heaven of neither thinking nor not thinking which may resemble a state of intuition. The realm of consciousness or knowledge without thought is reached (intuitive wisdom). Existence in this stage may last to 80,000 great kalpas. In this region, practitioners attain the plane of Neither perception-nor-Non-perception, mindfulness. They emerged from the attainment, they regard those things that are past, stopped and changed. Also, here practitioners, by passing entirely beyond the Sphere of No-Thingness, he reaches and remains in the Sphere of Neither-Perception-Nor-Non-Perception, which is beyond the plane of Nothingness.

In the Surangama Sutra, book Nine, the Buddha told Ananda about the four formless jhanas as follows: “Ananda! From the summit of the form realm, there are two roads. Those who are intent upon renunciation discover wisdom. The light of their wisdom becomes perfect and penetrating, so that they can transcend the defiling realms, accomplish Arhatship, and enter the Bodhisattva Vehicle. They are among those called great Arhats who have turned their minds around”. Heaven of the Station of Boundless Emptiness, those who dwell in the thought of renunciation and who succeed in renunciation and rejection, realize that their bodies are an obstacle. If they thereupon obliterate the obstacle and enter into emptiness, they are among those at the Station of Emptiness. Heaven of the Station of Boundless Consciousness. For those who have eradicated all obstacles, there is neither obstruction nor extinction. Then there remains only the Alaya Consciousness and half of the subtle functions of the Manas. These beings are among those at the Station of Boundless Consciousness. Heaven of the Station of Nothing Whatsoever. Those who have already done away with emptiness and form eradicate the conscious mind as well. In the extensive tranquility of the ten directions is nowhere at all to go. These beings are among those at the Station of Nothing Whatsoever. Heaven of the Station of Neither Thought nor Non-Thought. When the nature of their consciousness does not move, within extinction they exhaustively investigate. Within the endless they discern the end of the nature. It is as if were there and yet not there, as if it were ended and yet not ended. They are among those at the Station of Neither Thought Nor Non-Thought.

300. Four Heavenly Kings

There are four demonic-looking-figures deva kings in the first lowest devaloka (Tứ Thiên Vương). According to the myth, they dwell on the world mountain Meru and are guardians of the four quarters of the world and the Buddha teaching. They fight against evil and protect places where goodness is taught. These are four Heavenly (Guardian) Kings, or lords of the Four Quarters, who serve Indra as his generals, and rule over the four continents surrounding Mount Sumeru. The world we are residing now is under the Heaven of the Four Kings, and the Heaven which we can see directly is the Heaven of the Four Kings. First, Dhrtarastra (Dhatarattha p), Eastern Heaven King, a deva who rules over the Gandhabbas and keeps his kingdom (white color). The celestial musicians. Second, Virudhaka (Virulhaka p), Southern Heaven king who presides over the kumbhandas. Deva of increase and growth (blue color)—The gnomic caretakers of forests, mountains, and hidden treasures. Third, Virupaksa (Virupakkha p), the broad-eyed (ugly-eyed) deva (perhaps a form of Siva). Western Heaven king (red color) who rules over the nagas, demi gods in the form of dragons (những vị Trời Long Vương). Fourth, Vaisravana or Dhanada (Vessavana p), a form of Kuvera, a god of wealth. A deva who hears much and is well-versed. Northern heaven king (yellow color), ruler of the yakkhas or spirits.

301. Ten Good Actions and Deva-Gati

According to the Mahayana Buddhism, there are ten meritorious deeds, or the ten paths of good action. First, to abstain from killing, but releasing beings is good; second, to abstain from stealing, but giving is good; third, to abstain from sexual misconduct, but being virtuous is good; fourth, to abstain from lying, but telling the truth is good; fifth, to abstain from speaking double-tongued (two-faced speech), but telling the truth is good; sixth, to abstain from hurtful words (abusive slander), but speaking loving words is good; seventh, to abstain from useless gossiping, but speaking useful words; eighth, to abstain from being greedy and covetous; ninth, to abstain from being angry, but being gentle is good; tenth, to abstain from being attached (devoted) to wrong views, but understand correctly is good. According to the Vimalakirti Sutra, chapter ten, the Buddha of the Fragrant Land, Vimalakirti said to Bodhisattvas of the Fragrant Land as follows: “As you have said, the Bodhisattvas of this world have strong compassion, and their lifelong works of salvation for all living beings surpass those done in other pure lands during hundreds and thousands of aeons. Why? Because they achieved ten excellent deeds which are not required in other pure lands.” What are these ten excellent deeds? They are: using charity (dana) to succour the poor; using precept-keeping (sila) to help those who have broken the commandments; using patient endurance (ksanti) to subdue their anger; using zeal and devotion (virya) to cure their remissness; using serenity (dhyana) to stop their confused thoughts; using wisdom (prajna) to wipe out ignorance;putting an end to the eight distressful conditions for those suffering from them; teaching Mahayana to those who cling to Hinayana; cultivation of good roots for those in want of merits; and using the four Bodhisattva winning devices for the purpose of leading all living beings to their goals (in Bodhisattva development). According to Hinayana Buddhism, according to Most Venerable Narada, there are ten kinds of good karma or meritorious actions which may ripen in the sense-sphere. Generosity or charity which yields wealth; morality gives birth in noble families and in states of happiness; meditation gives birth in realms of form and formless realms; reverence is the cause of noble parentage; service produces larger retinue; transference of merit acts as a cause to give in abundance in future births; rejoicing in other’s merit is productive of joy wherever one is born; rejoicing in other’s merit is also getting praise to oneself; hearing the dhamma is conductive to wisdom; expounding the dhamma is also conducive to wisdom; taking the three refuges results in the destruction of passions, straightening one’s own views and mindfulness is conducive to diverse forms of happiness.

302. The Way

“Marga” means the way; however, according to Buddhism, “Marga” means the doctrine of the path that leads to the extinction of passion (the way that procures cessation of passion). In Buddhism, once talking about “Marga”, people usually think about the “Noble Truths” and the “Noble Path”. The “Noble Truths” is the fourth of the four dogmas. The Noble Path is the eight holy or correct ways, or gates out of suffering into nirvana. In Buddhism, “Marga” is described as the cause of liberation, and bodhi as its result. “Marga” is a Sanskrit term for “path” in Buddhist practice that leads to liberation from cyclic existence. According to the Sutra In Forty-Two Sections, Chapter 2, the Buddha said: “The Path of Sramanas who have left the home-life renounce love, cut (uproot) desire and recognize the source of their minds. They penetrate the Buddha’s Wonderful Dharmas and awaken to unconditioned dharmas. They do not seek to obtain anything internal; nor do they seek anything external. Their minds are not bound by the Way nor are they tied up in Karma. They are without thoughts and without actions; they neither cultivate nor achieve (certify); they do not need to pass through the various stages and yet are respected and revered. This is what is meant by the Way.” Cultivators who decide to follow the Buddha’s foot-step always think about the paths that lead to liberation. The first path is the “Path of accumulation” (Sambhara-marga skt). This is the first of the five paths delineated in Buddhist meditation theory, during which one amasses (tích trữ) two “collections”: 1) the ‘collection of merit’ (punya-sambhara), involves cultivating virtuous deeds and attitudes, which produce corresponding positive karmic results; and 2) the ‘collection of wisdom’ (jnana-sambhara), involves cultivating meditation in order to obtain wisdom for the benefit of other sentient beings. In Mahayana meditation theory, it is said that one enters on the path with the generation of the “mind of awakening” (Bodhicitta). The training of this path leads to the next level, the “path of preparation” (prayoga-marga). The second path is the “Path of truth”. According to the Platform Sutra of the Sixth Patriarch’s Dharma Treasure, the Sixth Patriarch, Hui-Neng, taught: “Good Knowing Advisors, the Way must penetrate and flow. How can it be impeded? If the mind does not dwell in dharmas, the way will penetrate and flow. The mind that dwells in dharmas is in self-bondage. To say that sitting unmoving is correct is to be like Sariputra who sat quietly in the forest but was scolded by Vimalakirti. Good Knowing Advisors, there are those who teach people to sit looking at the mind and contemplating stillness, without moving or arising. They claimed that it has merit. Confused men, not understanding, easily become attached and go insane. There are many such people. Therefore, you should know that teaching of this kind is a greater error.” The third path is the path leading to the end (extinction) of suffering, the fourth of the four axioms, i.e. the eightfold noble path. The Eightfold Path to the Cessation of Duhkha and afflictions, enumerated in the fourth Noble Truth, is the Buddha’s prescription for the suffering experienced by all beings. It is commonly broken down into three components: morality, concentration and wisdom. Another approach identifies a path beginning with charity, the virtue of giving. Charity or generosity underlines morality or precept, which in turn enables a person to venture into higher aspirations. Morality, concentration and wisdom are the core of Buddhist spiritual training and are inseparably linked. They are not merely appendages to each other like petals of a flower, but are intertwined like “salt in great ocean,” to invoke a famous Buddhist simile. If Buddhism does not have the ability to help its followers to cultivate the path of liberation, Buddhism is more or less a kind of dead religion. Dead Buddhism is a kind of Buddhism with its superfluous organizations, classical rituals, multi-level offerings, dangling and incomprehensible sutras written in strange languages which puzzle the young people. In their view the Buddhist pagoda is a nursing home, a place especially reserved for the elderly, those who lack self-confidence or who are superstituous.

In The Dharmapada Sutra, the Buddha taught: “The best of paths is the Eightfold Path. The best of truths are the Four Noble Truths. Non-attachment is the best of states. The best of men is he who has eyes to see (Dharmapada 273). This is the only way. There is no other way that leads to the purity of vision. You follow this way, Mara is helpless before it (Dharmapada 274). Entering upon that path, you will end your suffering. The way was taught by me when I understood the removal of thorns (arrows of grief) (Dharmapada 275). You should make an effort by yourself! The Tathagatas are only teachers. The Tathagatas cannot set free anyone. The meditative ones, who enter the way, are delivered from the bonds of Mara (Dharmapada 276). All conditioned, or created things are transient. One who perceives this with wisdom, ceases grief and achieves liberation. This is the path to purity (Dharmapada 277). All conditioned things are suffering. One who perceives this with wisdom, ceases grief and achieves liberation. This is the path of purity (Dharmapada 278). All conditioned things are without a real self. One who perceives this with wisdom, ceases grief and achieves liberation. This is the path of purity (Dharmapada 279). One who does not strive when it is time to strive, who though young and strong but slothful with thoughts depressed; such a person never realizes the path (Dharmapada 280). Be watchful of speech, control the mind, don’t let the body do any evil. Let purify these three ways of action and achieve the path realized by the sages (Dharmapada 281). Cut down the love, as though you plucked an autumn lily with the fingers. Cultivate the path of peace. That is the Nirvana which expounded by the Auspicious One (Dharmapada 285). In the Forty-Two Sections Sutra, the Buddha taught: “The Buddha said: “People who cherish love and desire do not see the Way. It is just as when you stir clear water with your hand; those who stand beside it cannot see their reflections. People who are immersed in love and desire have turbidity in their minds and because of it, they cannot see the Way. You Sramanas should cast aside love and desire. When the filth of love and desire disappears, the Way can be seen. Those who seek the Way are like someone holding a torch when entering a dark room, dispelling the darkness, so that only brightness remains. When you study the Way and see the Truth, ignorance is dispelled and brightness is always present.”

303. Three Paths